In Honor Of The Market Crash, Here Are 18 Meaningless Market Phrases That Sound Smart On TV

Meaningless?

Yes, meaningless.

Much of what these folks say will sound smart and sophisticated, but if you listen closely--and think about what you've just heard--you'll realize that the pundits aren't really saying anything.

(The art of sounding smart while saying nothing is critical to survival in a business in which folks are supposed to be able to predict the future. No one can reliably predict the future, so this supposition is ludicrous, but that doesn't stop everyone from trying.)

To prepare you for this onslaught, we're republishing our list of 16 Meaningless Market Phrases That Sound Smart On TV -- and adding a couple more that you hear especially often during a crash. You'll hear a lot of these over the next few weeks.

And, by the way, in case you're curious, here are the real reasons the market's crashing:

- Because stocks are expensive on one of the only valuation measures that is actually valid--"normalized" P/E ratios

- Because the global economy is deteriorating rapidly

- Because corporate profit margins are near record highs and therefore only have one way to go (down)

- Because interest rates are already near zero (hard for Fed to rescue us)

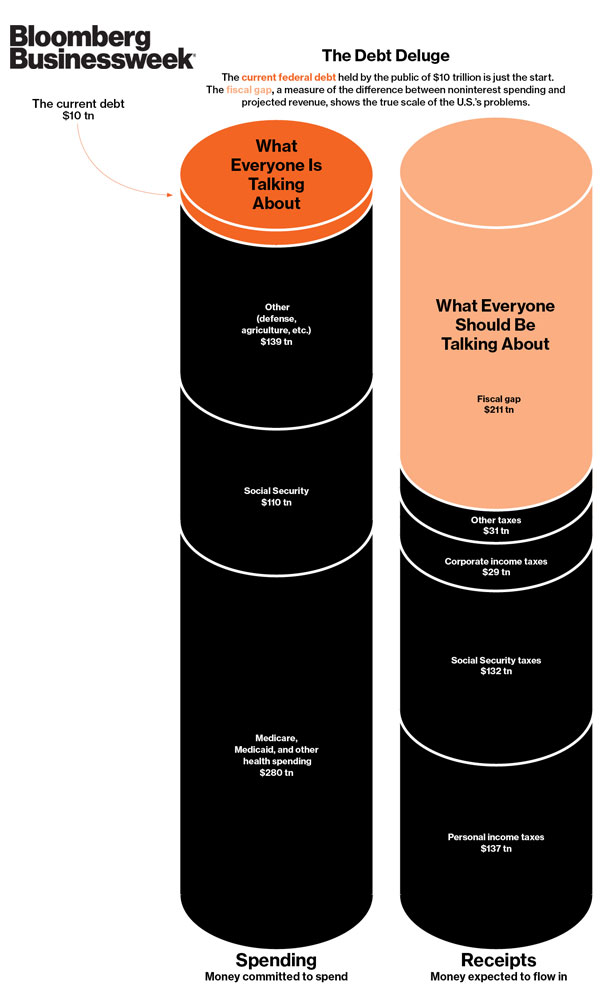

- Because the United States has not even begun to address its massive debt and deficit problem

- Because there's almost no way our government would approve another stimulus plan

- Because Europe is imploding, and there's just no way to save it for good without massive disruption and pain

- Because investors have gotten complacent and are now suddenly remembering that stocks are risky investments

But valuations are still high, the economy's still a mess, and the government is basically paralyzed, so it's not difficult to imagine that there will be more weakness ahead.

"Don't catch a falling knife"

When you'll hear it: When the market's dropping rapidly--like now.

Why it's smart-sounding: It implies wise, prudent caution. Stocks are dropping. No one knows where the bottom is. Obviously you shouldn't step in and buy because you'll just get clobbered.Why it's meaningless: Because no one ever knows where the bottom is. Sometimes stocks drop sharply...and then keep dropping sharply. Sometimes stocks drop sharply, and then rebound sharply--rewarding those who had the balls to buy while everyone else was selling. Except in hindsight, no one can tell the difference.

What's actually smart: As counter-intuitive as it sounds, the more stocks fall, the more attractive they become. American companies are not worth zero, so the closer stock prices get to zero, the more likely you are to be buying them at a discount to what the companies are actually worth (which, by the way, no one knows for certain, so don't get fooled into thinking that someone does). So the more that knife falls, the more you should want to try to catch it.

"You have to wait until you see the whites of the market's eyes"

When you'll hear it: In the middle of a market crash like this one.

Why it's smart-sounding: It suggests that there's a way to tell when the crash is about to be over--so you can safely buy in while everyone else is selling out. The idea is that, if you "wait until you see the whites of the markets eyes," you'll buy right at the moment of mass panic. Then, as soon as you have bought, there will be no more sellers left, and stocks will soar.Why it's meaningless: Because it's meaningless. "The whites of the market's eyes"? Give us a break. One alternate version of this concept--"wait until the 'puke point,'" is equally meaningless. All the way down in the market crash of 2008-2009, pundits talked about waiting for the "puke point." And when the market finally turned, without investors suddenly "puking" or without the market revealing the "whites of its eyes," everyone missed the move.

"Buy on weakness"

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't have the balls to say "buy" but wants to be able to say later that he/she told everyone to buy if the stock should happen to go up.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds highly informed. It sounds prudent (don't be stupid and chase the stock here). It sounds like common sense. It allows you to take credit for predicting any bullish move in the stock, while also being able to say "I said buy on weakness" if it crashes. It hedges all future outcomes.Why it's meaningless: It's too vague to be interesting or helpful. It can be applied to almost any stock or market at almost any time. It reveals that the speaker has little or no conviction about what he or she is saying and just wants to have it both ways.

"Sell on strength."

General: The corollary to "buy on weakness."

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't have the balls to say "sell" but wants to be able to say later that he/she told everyone to sell if the stock goes down.Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds highly informed. It sounds prudent (don't be stupid and sell the stock here, when it's already down). It will allow you to take credit for predicting any downward move in the stock, while also being able to say "I said sell on strength" if it soars. It hedges all future outcomes, at least over the near term--by implying that the stock will eventually trade higher than it is today, and lower.

Why it's meaningless: It's too vague to be interesting or helpful. It can be applied to almost any stock or market at almost any time. It reveals that the speaker has little or no conviction about what he or she is saying--and, instead, just wants to have it both ways.

"Take a wait-and-see approach"

General: A perennial favorite, especially when stocks are going down and worries are increasing.

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't have the balls to make any predictions or recommendations whatsoever.Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds prudent and cautious. It sounds appropriately skeptical. It plays to the viewer's sense that, somehow, things are more uncertain now than they usually are. (Absurd--the future is always uncertain.) It sounds like there's a specific event or events that you're waiting for that will suddenly turn you into the Donald Trump of Conviction, instead of suggesting that you're just perpetually wishy-washy. But it doesn't actually specify what this event or events are.

Why it's meaningless: It means nothing. How long are you going to wait? What are you waiting for? Why, when what you're waiting for finally arrives, won't everyone else see it at the same time and bid prices up or down? Why will the future be any less uncertain tomorrow, or next week, or next year, or whenever it is you're planning to "wait-and-see" until? What are you waiting for?

"The easy money has been made"

When you'll hear it: When a guest is asked whether investors should buy a market or stock that has already gone up a lot.

Why it's smart-sounding: It implies wise, prudent caution. It implies that you bought or recommended the stock a long time ago, before the easy money was made (and are therefore smart). It suggests that there might be further upside but that there might also be future downside, because the stock is "due for a correction" (another smart-sounding meaningless phrase that you can use all the time). It does not commit you to any specific recommendation or prediction. It protects you from all possible outcomes: If the stock drops, you can say "as I said..." If the stock goes up, you can say "as I said..."Why it's meaningless: It's a statement of the obvious. It's a description of what has happened, not what will happen. It requires no special insights or powers of analysis. It tells you nothing that you don't already know. Also, it's not true: The money that has been made was likely in no way "easy." Buying stocks that are rising steadily is a lot "easier" than buying stocks that the market has abandoned for dead (because everyone thinks you're stupid to buy stocks that no one else wants to buy.)

"I'm cautiously optimistic."

A classic. Can be used in almost all circumstances and market conditions.

When you'll hear it: Pretty much anytime.Why it's smart-sounding: It implies wise, prudent caution, but also a sunny outlook, which most people like. (Nobody likes a bear, especially in a bull market). It sounds more reasonable than saying, for example, "the stock is a screaming buy and will go straight up from here." It protects the speaker against all possible outcomes. If the market drops, the speaker can say "As you know, I was cautious..." If the market goes up, the speaker can say, "As you know, I was optimistic."

Why it's meaningless: It's too general to mean anything. It could have accurately described any market outcome in history, merely by adjusting the unspecified time frame. (If you were "cautiously optimistic" in 1929, you were "cautious," which was good, and you were also optimistic, which was also good. Eventually, the market recovered!)

"It's a stockpicker's market."

Another classic. Sounds smart, but is completely meaningless.

When you'll hear it: Especially useful in bear markets or flat markets, but can be used anytime.Why it's smart-sounding: It suggests that the current market environment is different from other market environments and therefore requires special skill to navigate. It implies that the speaker has this skill. It suggests that, if you're talented enough to be "a stockpicker," you can coin money right now--while everyone else drifts sideways or loses their shirts.

Why it's meaningless: If you pick stocks for a living (or for your personal account), all markets are "stockpickers' markets." In all markets, traders are trying to buy winners and sell dogs, and in all markets only half of these traders succeed. (It's a different half each time, of course--and most of the "winnings" of the winners are wiped out by transaction costs and taxes, but that's a different story). It is no easier (or harder) to win the stockpicking game in a flat or bear market than in a bull market, and if you try, you'll almost certainly do worse than if you had just bought an index fund.

"It's not a stock market. It's a market of stocks."

When you'll hear it: All the time.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds deeply profound--the sort of wisdom that can only be achieved through decades of hard work and experience. It suggests the speaker understands the market in a way that the average schmo doesn't. It suggests that the speaker, who gets that the stock market is actually a "market of stocks," will coin money while the average schmo loses his or her shirt.Why it's meaningless: Because it's a statement of the obvious. Of course it's "a market of stocks." But it's also a "stock market." And viewing the stock market as a "market of stocks" doesn't help you in any way, other than reminding you that all stocks don't move up and down the same amount. (See: "It's a stockpickers' market.")

"We're constructive on the market."

When you'll hear it: All the time.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds generally optimistic, which viewers will like, but it doesn't commit you to any specific recommendation or prediction or time period. It doesn't even require you to to say that the market will go up or down or how you are investing or think the viewer should invest. It just sounds generally optimistic, and it leaves you plenty of wiggle room if the market suddenly tanks.Why it's meaningless: Because being generally optimistic about the market over some unspecified time period is no different than being generally optimistic about life over some unspecified time period: Odds are, whatever happens, life will go on and the world won't be destroyed by an asteroid. And, besides, you're not even saying you're "optimistic." You're saying you're "constructive." That can mean anything!

That's Business Insider's Katya Wachtel in the screenshot above, by the way. She would never say anything as mealy-mouthed as "constructive."

"Stocks are down on 'profit taking'"

When you'll hear it: When a guest is asked to explain why the market (or a stock) is down after a strong run.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds like you know what professional traders are doing, which makes you sound smart and plugged-in. It sounds like common sense: Traders have made a lot of money--now they're "taking profits." It doesn't commit you to a specific recommendation or prediction. If the stock or market goes down again tomorrow, you can still have been right about the "profit taking." If the stock or market goes up tomorrow, you can explain that that traders are now "bargain hunting" (see next smart-sounding meaningless phrase).Why it's meaningless: Traders buy and sell stocks for dozens of reasons. And for every seller, at any time, there is a buyer on the other side of the trade. Whether or not the seller is "taking a profit"--and you have no way of knowing--the buyer is at the same time placing a new bet on the stock. So collectively describing market activity as "profit taking" is ridiculous. Any trade, at any time, in any market, can be described as "taking a profit" or "cutting a loss" or "bargain hunting" or "filling out a position," and so on. You have no way of knowing what's actually going on, and there's always someone on the other side of every trade. But no one will ever prove you wrong!

That's Business Insider's Joe Weisenthal on the left. He knows better than to say "profit taking."

"Stocks are up on 'bargain hunting'"

General: The corollary to "profit taking."

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest is asked to explain why the market (or a stock) is up after a period of weakness.Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds like you know what professional traders are doing, which makes you sound smart and plugged-in. It sounds like common sense: Traders have been sitting on the sidelines waiting for the market to fall--and now they're "bargain-hunting." It doesn't commit you to a specific recommendation or prediction. If the stock or market goes down again tomorrow, you were still right about the "bargain hunting." If the stock or market goes up tomorrow, you can explain that that traders are now "taking profits" after yesterday's "bargain hunting."

Why it's meaningless: Again, traders buy and sell stocks for dozens of reasons. And for every buyer, at any time, in any market, there is a seller on the other side of the trade. Whether or not the buyer is buying because he or she thinks they have found a "bargain"--and you have no way of knowing--the seller is at the same time ditching the stock, perhaps because he or she is "profit taking." So collectively describing this activity as "bargain hunting" is ridiculous. Any trade, at any time, in any market can be described as "taking a profit" or "cutting a loss" or "bargain hunting" or "filling out a position," and so on. You have no way of knowing what's actually going on. But no one will ever prove you wrong!

"More buyers than sellers"

When you'll hear it: When a guest is asked to explain why the market (or a stock) is going up.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds like you know what's really going on, which makes you sound smart and sophisticated. It sounds like you understand how the market works, in a way that Joe Schmo doesn't. (Ahh...there are more buyers than sellers! Insightful! Fascinating!)Why it's meaningless: In every trade--every one--there is exactly one buyer and exactly one seller. You cannot buy a stock without having someone sell it to you. To say that the market or a stock is going up because there are "more buyers than sellers," therefore, is not just meaningless, it's wrong. What is actually happening when a stock or market ticks up is that the next buyer is willing to pay more for the stock or market than the last buyer was. What is actually happening when the market or a stock goes down, meanwhile, is that the next buyer is not willing to pay as much for the market or stock as the last buyer was. There are never "more buyers than sellers" or "more sellers than buyers." There are simply different price levels at which a buyer and a seller are willing to trade.

"There's lots of cash on the sidelines"

General: A classic way to suggest that the market will eventually go up.

Alternates: "Dry powder."When you'll hear it: Any time a guest needs to explain a bullish outlook.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds like common sense: Wimpy investors are hoarding cash instead of "putting it into the market." When these investors finally grow a pair and use their cash to buy stocks, the market will go up.

Why it's meaningless: There is no such thing as cash "going into the market" or "coming out of the market." In every trade--every one--a seller sells stock to a buyer in exchange for cash. Importantly, the cash used to buy the stock does not go "into the market." It goes to the seller. After the trade, the seller now has cash instead of the stock, and the buyer now has the stock instead of cash--and the overall amount of neither cash nor stock has changed. At some times, some investors--mutual funds, for example--might have more cash than usual in their funds (for a variety of reasons), and this cash might eventually be used to buy stocks, but this cash will not go "into the market." It will go to the investors who own the stocks that the mutual funds buy. In short, again, cash does not go "into" and "out of" the market. Someone always holds the cash, and someone always holds the stocks. So, in a literal sense, the cash is always "on the sidelines."

"We're in a bottoming process."

General: A classic way to describe a stock or market that has fallen a lot and might do anything from here.

Alternates: "Forming a base." "Bumping along the bottom."When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't know what a stock will do but wants to imply that it might eventually go up but hedge him or herself by saying that it also might go down.

Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds highly informed. The stock is "in a bottoming process." It's "forming a base." It sounds reassuring, without being too precise. Sure, the stock might drop some more, you seem to be saying, but it's generally settling in here--and then it will eventually go up. It sounds like you have command of "technical analysis," which almost always sounds smart (and is almost always meaningless).

Why it's meaningless: Because it describes a price pattern that has happened but does not tell you anything about what will happen. A drop followed by a sideways move does not mean the stock won't drop more. It also does not mean the stock will go up. And it commits to no time frame. It can be used to describe any stock that has moved sideways for a while, without offering the slightest insight into the future.

"Overbought"

General: Another classic way to describe a stock or market that has gone up a lot.

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't know what a stock or market will do but wants to sound generally bullish while also implying that the stock might be "due for a correction" (also meaningless).Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds highly informed. It sounds like common sense: The stock just went up a lot--so it must be "overbought." It hedges all future outcomes. (Just because it's "overbought" doesn't mean it will go down. What if it gets more "overbought"?) It sounds like you have command of "technical" and "quantitative" analysis, which always sounds smart--even though they're almost always meaningless.

Why it's meaningless: What does "overbought" mean, exactly? Does it mean that traders bought too much of the stock? How can they have done that--the amount of stock in the market didn't change. Does it mean that traders paid too-high prices for the stock? Okay, maybe it means that. But does that mean the stock is going to go down soon? Why? In short, it's a fancy and sophisticated-sounding way of saying nothing.

"Oversold"

General: The corollary to "overbought." A classic way to describe a stock or market that has gone down a lot.

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't know what a stock or market will do but wants to imply that it might go up.Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds highly informed. It sounds like common sense: The stock just went down a lot--it must be "oversold." It hedges all future outcomes. (Just because a stock or market is "oversold" doesn't mean it will go up. It might get more "oversold.") Again, it sounds like you have command of "technical" and "quantitative" analysis, which always sounds smart.

Why it's meaningless: As with "overbought," what does it mean, exactly? Does it mean that traders sold too much of the stock? How can they have done that--the amount of stock in the market didn't change. Does it mean that traders sold stock at prices that were too low? Okay, maybe it means that. But does that mean the stock is going to go up soon? Why? In short, it's a fancy and sophisticated-sounding way of saying nothing.

"It's a show-me stock"

General: A classic way to describe a company that has blown it.

When you'll hear it: Any time a guest doesn't know what a banged-up stock will do next--especially if he or she is worried that viewers might think he or she was dumb enough to have owned it when it cratered.Why it's smart-sounding: It sounds tough, decisive, and judgmental. You're not going to take management's word for anything--not like those other idiots who just got blown up in the stock. You want to see the results. You want to make management show you that they can deliver, before you entrust them with your clients' hard-earned money.

Why it's meaningless: All stocks are "show me" stocks. If management "shows you" that they have delivered results that beat the market's expectations, the stock usually goes up. If management "shows you" that they have blown the quarter, the stock tanks. Even when applied to the limited realm of companies that have just choked, if management "shows you" that they can deliver, they'll show everyone else, too. The stock will go up before you can buy it. And then, once the stock goes up, management will have to "show you" that they can continue to do better. And so on. By the time you and everyone else finally trust management enough again to buy into their vision of the future, the stock will have soared--and it will then be time for management to show you that they've blown it again.

And sometimes, of course, no matter how smart you sound on TV, the producers will make you look like a sex-crazed zealot

But there's not much you can do about that

Leaders from EU powerhouses Germany and France will hold talks today (5 August) after a global market rout roused fears that Europe's debt crisis is spinning out of control and the US recovery is stalling.

Belying a sense of crisis, many of Europe's policymakers are still on summer holidays, although EU Economic and Monetary Affairs Commissioner Olli Rehn broke away from his to return to Brussels, where he is planning a news conference today (Friday).

French President Nicolas Sarkozy will discuss financial markets with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Sarkozy's office said in a statement.

The heavy sell-off came after the European Central Bank failed to include Italy and Spain in a fresh round of bond buying, as yields on their debt shot above 6 percent, the highest level since the euro was launched over a decade ago.

ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet said there was not full support in the central bank for the action, underscoring deep divisions within Europe over how to handle a debt crisis that has forced Greece, Ireland and Portugal to seek financial rescues, Reuters reported.

Investors are concerned that Italy and Spain, the euro area's third- and fourth-biggest economies, could be next.

Sarkozy said France, Germany and Spain had talked to Trichet.

Investors had hoped the ECB would target Spanish and Italian debt in reviving its bond-buying stimulus program, but it restricted the purchases to Irish and Portuguese securities.

No longer crisis of EU's periphery

Yesterday, Commission President José Manuel Barroso sent an unusual letter to euro zone leaders, asking for a re-foundation of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which the EU set up in May 2010 at the height of the Greek crisis, as well as the ESM, its extension which will be enshrined in EU treaties. Last March leaders decided that the ESM will in total hold €700 billion to shield eurozone countries from future debt crises.

"It is clear that we are no longer managing a crisis just in the euro-area periphery," Barroso wrote. Without naming Italy or Spain, he urged "a rapid re-assessment of all elements related to EFSF" and proposed that leaders should decide "how to further improve the effectiveness of both the EFSF and the ESM in order to address the current contagion".

Barroso also deplored "the undisciplined communication" of EU leaders and "the complexity and incompleteness of the 21 July package", namely the decisions of the recent euro zone summit which he personally presented as a major breakthrough at the time.

US problems compound uncertainty

In the United States, a similar sense of political paralysis reins.

Just days after a bitterly fought, last-minute deal to raise the country's debt ceiling and avoid default, realisation has sunk in that many elements of the $2.1 trillion deficit reduction plan are short term and not locked in place.

Doubt has spread through markets that Congress will stick to implementing it in full after the November 2012 elections.

This, combined with a bout of poor economic data, points to a heightened risk of another slump. Lawrence Summers, a senior adviser to the U.S. president until last year, argued in a Reuters column that there is a one-in-three chance of recession in the United States.

US employment numbers due later on Friday will be critical to market sentiment. Forecasts are for a tepid 85,000 jobs added in July, but a weak number or even contraction would boost concern that the United States is heading into recession.

Many economists say chances are slim that Congress would endorse a further round of fiscal stimulus now that it is focusing on fiscal spending cuts.

"I don't see a well functioning government that can do something," said Jeff Frankel, economics professor at Harvard University and former White House economic advisor under Bill Clinton. "If everything is blocked politically, especially fiscal policy, there's nothing much you can do."

POSITIONS:

EFSF resources will not be sufficient to bail out a large country, Julien Beauvieux argues in an editorial in the French daily La Tribune. He claims EFSF financial capacity should be increased to the level of about €2 trillion in order to restore its credibility.

The ability of the EFSF to act is hampered by its member countries, who have not yet ratified its establishment, and this ratification is not expected before September, according to experts. The EFSF should rapidly start buying sovereign debt to contain speculation and limit contagion, he argues.

France needs to act quickly since the crisis is not limited to the euro zone periphery, argues Jean-Marc Vittori in the French Daily Les Echos. But Commission President José Manuel Barroso has no credibility whatsoever and the results of the 21 July euro zone summit are not yet operational, he argues.

France has every interest in the world in doing its utmost to overcome these obstacles, because the barometer is already signalling the impending storm headed its way, he writes. On Wednesday, the interest rate on France's sovereign debt was exceeded Germany's by 0.79%, he stressed that this was something which had never happened before.

Only the ECB can halt euro zone contagion, argues Paul De Grauwe, writing for the Financial Times.

He compares bond markets with banking systems, in which the instability of one bank is usually solved by mandating the central bank to be a lender and to print money.

The EFSF will never have the necessary credibility to stop contagion because it cannot actually print money, De Grauwe argues.

Instead an overhaul of the of the euro zone institutions is urgently needed, the most important being the ECB, which needs to take on full responsibility as lender of last resort in the government bond markets of the euro zone, he argues.

In Honour of the crash, 18 meaningless phrases..

http://www.businessinsider.com/meaningless-market-phrases?op=1

http://www.businessinsider.com/meaningless-market-phrases?op=1

Is the Maharashtra government dillydallying on ordering a CBI inquiry into the issue of the alleged illegal sale of Waqf land to industrialist Mukesh Ambani for his 27- storey ultra luxury home that is worth nearly $ 2 billion? The state government had received a letter from the Union government in June, asking it to consider ' referring' the matter to the premier investigating agency to probe the land deal. The state has, however, not taken any decision on the matter yet.

The land deal on Mumbai's posh Altamount Road has been embroiled in a controversy ever since Ambani began building his multistorey residence Antillia. On Monday, the issue was raised in the state assembly by Opposition leader Eknath Khadse.

He said the Rs 500- crore plot was shown to have been sold by the Karimbhai Ibrahimbhai Khoja Charitable Trust for just Rs 21 crore. The piece of land was originally reserved for educating children of the Khoja Muslim community.

Maharashtra's minority affairs minister Arif Nassim Khan said the state had received a letter from the Centre and had sought the opinion of the law and judiciary department.

" The legal department conveyed its opinion to the state home department on July 25," Khan said. But he did not reveal what the law department's stand was.

Khan further said a notice was served to the trust by the Maharashtra government in 2004 over the transaction. It was, however, withdrawn after the state got ` 16 lakh from the trust to regularise the deal.

Maharashtra home minister R. R. Patil said he would comment on the matter only after seeing the opinion given by the law and judiciary department.

This Waqf land deal has sparked rows earlier, too. In 2007, then minority affairs minister Anish Ahmed had mentioned a number of irregularities in the sale of the land and had asked the Maharashtra State Waqf Board to take back the plot. However, in a curious development, while the minister kept claiming the sale was illegal, then chief minister Vilasrao Deshmukh said there were no irregularities in the deal.

Incidentally, Ambani has still not started living in Antillia.

Articles in this series are exploring the extent and impact of corporate secrecy in the United States.

NEW YORK - A spate of spectacular collapses of Chinese stocks listed on American exchanges has cost U.S. investors billions of dollars. The fiasco has sparked multiple investigations. Accusations are swirling in Washington and Beijing.

It all began with an email sent out of the blue a decade ago to a Texas businessman named Timothy Halter.

The email came from Shanghai native Zhihao "John" Zhang. The former medical student introduced himself and asked: Was Halter interested in helping bring Chinese companies to the U.S. stock market? Zhang proposed using a backdoor method that the Texan had mastered for American firms: buying dormant shell companies listed on U.S. exchanges. Soon, Halter and Zhang brought two Chinese firms to market in America: a manufacturer of power-steering systems and a maker of vitamins, weight-loss supplements and household cleaners

The email led to a boom for a niche industry of advisers who specialize in a brand of deals, called the "reverse merger," that use shell companies to give clients easy entry into U.S. capital markets. More than 400 Chinese companies seized the chance.

Leading the way was Halter, a slim, salt-and-pepper-haired man who played a direct or indirect part in 23 deals; staked his name on at least 20 other deals done by his Shanghai partner, Zhang; and paved the way, through conferences in China, for dozens of other deals.

It was a lucrative gambit: Halter lives with his family on a 50-acre ranch in Texas, where he breeds bass.

His firm, Halter Financial Group, threw splashy "summits" to promote the industry, including a gathering headlined by former President George W. Bush in 2010. Its website boasts: "Reverse Merger Experts!"

But deals birthed by Halter and his imitators are now blowing up.

Investors have alleged widespread accounting irregularities and other problems at dozens of the Chinese companies that reverse-listed in the U.S., causing share prices to nosedive. Since March, some 30 Chinese firms have seen their auditors resign and at least 25 have been delisted from U.S. exchanges.

$18 BILLION GONE

A Reuters examination of a cross-section of 122 Chinese reverse mergers on U.S. markets found that between each stock's peak trading price and July 10, 2011, those companies saw a total of $18 billion of their market capitalization vanish.

Reuters interviewed nearly 100 industry participants and examined financial records of dozens of Chinese companies to paint the most detailed picture yet of the network of dozens of players involved in the reverse-mergers boom.

That industry hinges on a handful of leading "shell brokers" such as Halter who purvey paper companies; investment banks who specialize in financing a firm after a reverse merger; and auditors, usually small shops, who are lightly regulated in the U.S.--and not at all in China and Hong Kong. The controversy has stirred up new tensions between Washington and Beijing, which held talks on the matter in July. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the U.S. auditing watchdog, issued a report in March about potential problems with the audits of Chinese companies formed through reverse mergers. The Securities and Exchange Commission has set up a working group to examine Chinese reverse mergers, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation has opened its own broad investigation, say people familiar with the situation.

The Chinese reverse-merger boom and bust offer insight into a little-understood corner of American business: the widespread use of shell companies, which can offer their owners a way to minimize regulatory scrutiny. The U.S. in recent years has called for much greater transparency in global business transactions. But on American shores, opaque shell companies are rife.

"It appears that some Chinese firms have seen a way to access the strongest public markets in the world, but through the weakest area of enforcement," says Republican Rep. Patrick McHenry, a member of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

REVERSE GEAR

A reverse merger hinges on a shell company-a firm without meaningful assets or operations, used as a vehicle for transactions-that's already listed on a stock exchange.

A deal typically starts with a so-called shell broker, anyone from a small shop to a larger firm such as Halter's. Brokers acquire shells, often domiciled in a secrecy-friendly state such as Delaware, Utah or Nevada. The broker then sells the U.S. shell to an operating company seeking to trade on a U.S. exchange-a transaction which, unlike an initial public offering, isn't overseen by regulators.

The acquiring firm thus becomes a publicly-traded company, with access to U.S. investors - but without the time, expense and scrutiny of a traditional initial public offering. Companies are incorporated under state rather than federal law, and so the federal overseer of stock flotations, the Securities and Exchange Commission, doesn't as a matter of course review reverse mergers until after the deal is done.

In Chinese deals, the buyer is often a holding company based in Delaware, the British Virgin Islands or other tax haven, which in turn controls the actual operations on mainland China. This structure complicates the ability of U.S. regulators to dig into the accounts of the resulting firms.

In recent years, one in three U.S. reverse mergers involved a Chinese operating company. In 2010, 260 reverse mergers were completed, according to deal tracker PrivateRaise. Of those, 83 deals involved operating companies in mainland China.

There are more than 1,200 dormant public companies in the U.S., PrivateRaise says. They can be purchased for as little as $30,000, then sold by shell brokers for as much as 10 times that amount or more. Brokers say that in 2007 and 2008, the peak of the market, Chinese firms would pay up to $800,000 for a high-quality shell, one with no lingering liabilities. Reverse mergers, to be sure, are a legitimate way to gain access to capital for smaller companies that can't afford a full-fledged initial public offering or don't need to raise large sums. The problem isn't the technique, defenders argue, but rather people who misuse it.

David N. Feldman, a New York lawyer and author of a book about reverse mergers, notes that the large majority of Chinese deals are good ones, and that IPOs are also subject to abuses. Chinese software maker Longtop Financial Technologies Ltd. achieved a peak market value of $2.3 billion on the New York Stock Exchange after its IPO, but came under regulatory scrutiny this spring and is now being de-listed from the Big Board.

COLORADO ROOTS

The industry has roots in the Colorado mining boom and bust of the 1950s, when entrepreneurs bought up failed listed companies. Timothy Halter's breakthrough was to spread the tactic to China. Halter, the founder and president of boutique firm Halter Financial Group in Argyle, an affluent suburb northwest of Dallas, did a handful of reverse mergers, all for American companies, in the seven years after opening his company in 1995.

Zhang, who lived in Toronto, found Halter by Googling "reverse mergers," according to people who know both men. China was the world's hottest economy, and Halter was intrigued by Zhang's email and subsequent calls, these people say.

Their first Chinese reverse mergers-involving household cleaning-goods maker Tiens Biotech in 2002 and China Automotive in 2003--caused a sensation.

"These were the two deals that really got everybody's attention," said Beau Johnson, managing director of Chinamerica Holdings, a financial advisory and investment fund in Richardson, Texas, which owns shells and has done several Chinese reverse mergers. "The industry just snowballed from there."

After the first two deals, the Texan sent Zhang back to Shanghai to open an outpost and scout Chinese firms ripe for an American listing. Zhang, who once aspired to be a doctor and graduated from Fudan University Medical School in 1990, began scouring China for businessmen who dreamed of ringing the opening bell on Nasdaq. He set up New Fortress Group Ltd., a British Virgin Islands entity, to take stakes in deals. Zhang declined to comment for this article.

'PRESTIGE AND CREDIBILITY'

Halter gained note as a guru on the nascent market for Chinese mergers-and touted his new Halter USX China Index, the first to track Chinese companies trading on U.S. exchanges. In 2004, he told a Congressional panel on China that "there is prestige and credibility in a US listing. It is also understood by Chinese companies that our standards are high and it is not an easy task to comply with the requirements to be a public company in the U.S."

In 2008, Halter trademarked in the U.S. his secret sauce: a transaction he dubbed the APO, or Alternative Public Offering. It combined a reverse merger and a financing arrangement called a private investment in public equity, or Pipe, that allowed firms to go public and raise money in one fell swoop. Halter's trademark application said he had "instructed hundreds of attorneys, CPAs and professionals about the reverse merger process."

Reuters identified 17 deals arranged by Halter Financial Group, and six in which Halter brokered the shells used in transactions orchestrated by others. The firm consulted dozens more Chinese companies on preparing to go public, introducing them to auditors and lawyers needed for the deals. People in the industry estimate Halter has had a hand, direct or indirect, in one in eight Chinese deals listed on American exchanges.

Halter's deals sometimes use a dizzying array of shells. His firm arranged a reverse merger in 2010 for Long Fortune Valley Tourism, a Chinese company that describes itself as focused on "cave tourism." The merger involved shell companies in Texas, Delaware, Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands. The original shell used in the deal was created years earlier by Halter to buy up a bankrupt chain of nursing homes.

In addition to taking stock in the shells used in his transactions, Halter also earned "finder's fees" through his affiliated broker-dealer firm, Halter Financial Securities. HFS referred Chinese companies to investment banks, which then raised money for them.

'MIAMI GLAM'

One of the leading banks in the game was Roth Capital Partners of Newport Beach, California. Led by Chairman Byron Roth, its specialty is to provide financing to Chinese clients after a reverse merger. Roth says it has raised more than $3 billion for U.S.-listed Chinese companies. Such deals accounted for nearly half of the $1.9 billion in capital Roth raised for clients in 2009. Roth's heady success was reflected in the glitzy conferences it threw for the industry. In March, more than 3,000 hedge-fund managers, accountants, lawyers, bankers and financial advisers flocked to the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Dana Point, southern California.

Just hours after the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board issued its warning about Chinese reverse mergers, Roth threw a wear-only-white "Miami Glam" party in an elegant tent. Guests stood surrounded by rhinestone-encrusted sculptures of leopards. Bikini-clad hostesses served cotton candy as rapper Pitbull put on a concert. For the more conservative Chinese guests, Roth organized a lavish banquet nearby at the posh Resort at Pelican Hill.

"They don't like our food. And they don't like rap," explained one organizer.

Not all of Roth's deals have stood the test of time. One client, China Biotics, a maker of so-called pro-biotic food products, delisted from NASDAQ in June, 19 months after Roth helped it raise more than $79 million from investors. China Biotics' auditor resigned amid accusations that the company forged documents and created a fake website that overstated its cash holdings. Byron Roth, Roth's chief executive, declined to comment.

THE ACCOUNTING TRAIL

Just as crucial to the industry were the accountants. To do a reverse merger, the acquiring company needs to hire an auditor registered with the PCAOB.

It became common for small audit firms far from China, often with no affiliates in the country, to sign off on books and records kept halfway around the world. In the U.S., the PCAOB reviews small auditing firms only once every three years.

In Bountiful, Utah, the small firm of Chisholm, Bierwolf and Nilson used its experience with U.S. shell companies to win referrals to a global client base. From a suburb of Salt Lake City, the firm audited clients in China-and South Korea, Bolivia, El Salvador and Kazakhstan as well. CBN was a deal, charging about half the going rate for a comparable sized firm in New York or California. "We didn't ever have to do any advertising," said Todd Chisholm, a former managing partner at CBN.

Todd Chisholm prospered. An avid golfer, he and his then-wife built a $1 million home on a golf course not far from his Bountiful office. In 2006, Chisholm got a referral to a company called Hendrx, formed in 2004 through a reverse merger with a U.S. shell, with primary operations in China, according to Chisholm and two others directly involved.

Hendrx described itself as a manufacturer and distributor of devices that purify, filter and generate water from moisture in the air. But the business wasn't making money, executive turnover was high, and Hendrx had been sued for alleged contractual fraud and patent infringement, SEC filings show.

Over the next four years, Todd Chisholm audited Hendrx's books, giving a clean bill of health, though noting questions about the company's ability to continue as a going concern. Once a year, he visited the Chinese operations for week-long reviews.

The PCAOB later found these audits to be grossly inadequate. According to an April 8 PCAOB disciplinary order, Chisholm and his partner, Troy F. Nilson, were each auditing on average 25 companies in 2006 and 2007. About half of those were shell companies, Chisholm says.

Neither Chisholm nor Nilson spoke Chinese, the PCAOB noted, and they relied on less-experienced native-speaking staff in the audit process. In January 2009, Hendrx lost its final appeal of the patent infringement case and, unable to pay a $1.2 million judgment, turned over ownership of all its operations to its creditors. Worth $37 million at its peak, Hendrx has lost nearly all its value, its thinly traded shares now fetching less than a penny apiece on the Over the Counter market.

The PCAOB found the audits at Hendrx and three other clients so troubled that it barred Todd Chisholm and his namesake firm from auditing U.S.-traded companies for life. His partner, Nilson, was banned for at least five years. Chisholm acknowledges that his staff was stretched thin, but stands by the effectiveness of the audits. Nilson didn't reply to requests for comment. Despite his ban by the PCAOB, Chisholm is working on four or five planned Chinese reverse mergers through a new consulting firm, Fairway Mergers Inc. He says he is no longer acting as auditor of their financial statements, but is advising the companies and their investors on their numbers and how to prepare for a U.S. audit.

"I'm very much enjoying not being an auditor. I don't see myself ever going back there," Chisholm says. In the new venture, "I've got talent and expertise that I can use."

HALTER'S REVERSAL

Last year in Shanghai, where he had built up a staff of 40, Halter staged his own answer to rival Roth Capital's gatherings. His firm brought in former President George W. Bush and former Bush Treasury secretary John Snow as featured speakers on the global economy. Spokespeople for Bush and Snow declined to comment.

This year, the boom turned bust. Last summer, short sellers, who bet that a share will decline in price, began targeting Chinese reverse merger stocks. Those stocks started crumbling, regulators began opening probes, and a host of auditors resigned, often citing concerns about cash balances and management integrity. Three companies Halter has worked with are among those that hit the rocks.

ShengdaTech, a KPMG-audited chemicals maker in which Goldman Sachs took a 7.6 percent stake, saw auditor KPMG resign in April, citing "serious discrepancies" in its bank statements and representations of customers. ChinaAgritech, a fertilizer maker that garnered investments from private-equity giant Carlyle Group, was delisted from Nasdaq in May for not filing its annual report on time, three months after a short seller said a visit had shown the company's factories idle and suppliers non-existent.

Also in trouble is China Automotive, one of the two Halter deals that set off the boom.

In April 2007, the PCAOB issued a report faulting China Automotive's Toronto-based auditor, Schwartz Levitsky Feldman, for "deficiencies of such significance that it appeared to the inspection team that the firm did not obtain sufficient competent evidential matter to support its opinion on the issuer's financial statements." The agency did not identify the audit clients in question, but last April it reported finding the same problems in a new inspection.

In December, Schwartz Levitsky Feldman resigned as China Automotive's auditor. In March, the company said it would restate earnings for 2009 and the first three quarters of 2010. That drew a warning from Nasdaq that it was in danger of not being compliant with SEC requirements on timely filing of financial reports. China Automotive did manage to submit its filings, but has seen its stock fall by two-thirds since January 2010, wiping out $471 million in market value.

Halter has not been accused by the SEC or PCAOB of any wrongdoing. "Our business model is to work with the companies that seek to access the US capital markets and that represent to us that they meet certain financial requirements," Halter said in an email in response to queries. "We then introduce these companies to PCAOB-registered accounting firms and multinational law firms."

A NEW WORLD

The world that Timothy Halter helped create may be in for serious change.

In recent months, the SEC has begun taking a much closer look at the filings that follow a reverse merger, according to investment bankers and lawyers whose clients are being reviewed. The agency has suspended trading in at least three stocks. Representatives from the SEC and the PCAOB recently visited China to discuss better cooperation on the auditing side. John Zhang, still in Shanghai, is focusing on getting Chinese firms listed in Germany and Hong Kong. A spokesman declined to provide further details about his work or his early career. Timothy Halter, for his part, is distancing himself from the industry.

"Our model has not changed," he told Reuters in an email exchange. But he did "not anticipate doing any Chinese APOs in the near future." Last month, Tiens Biotech, one of Halter's two breakthrough Chinese clients, said it was changing course. It's now de-listing and taking itself private.

The method? A series of mergers--with shell companies registered in Delaware and the British Virgin Islands.

The country's largest telecom service provider Bharti Airtel on Monday proposed an annual pay package of up to Rs 70 crore for chairman Sunil Mittal.

The company has sought shareholders approval for the same in the annual report released on Monday.

This will be more than double his last fiscal remuneration of Rs 27.5 crore, which is about 76% of the combined pay package of all directors in fiscal ended March 31, 2011.

As per the annual report, Mittal's remuneration rose by Rs 4 crore or 17% from his 2009-2010 fiscal's package of Rs 23.5 crore. Bharti Airtel also sought its shareholders' approval for re-appointment of Mittal as its managing director for another five-years with effect from October 1, 2011.

"This does not mean that Mittal's salary would be increased to Rs 70 crore. The company has sought approval so that one need not go to the board every time," said a company official.

Salman Khan worth Rs 50 crore now!

After the recent success of his movies, Salman Khan has hiked his price to Rs 50 crore. The actor who was charging 40 crore for a movie will now take home a whopping amount of Rs 50 crore. With Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan taking full control of their box-office successes and turning it into a financial gold mine, how can Salman Khan be left behind? The actor enjoying his recent success run in Bollywood, with two back to back hits in Dabangg and Ready.

Filmmaker Bhushan Kumar told Jha that Salman's price has been re-structured for his next movie. "When Salmanbhai did" Ready" the film industry was facing a huge financial crunch. But he agreed to cut down his price from Rs 40 crore to Rs 17 crore. This was the only way we could have made Ready at that time. Now the market has changed for the entire film industry. So, we are currently re-negotiating with him for our next film."

It is said that Salman has not only hiked his fee but also has started taking interest in the unit of the film and the cast. "Salman is not only quoting a fee close to Rs 50 crore, he is also 'recommending' (Ready: appointing) directors for these films. Like, for the T Series project Salman has put forward the names of two directors and has asked producer Bhushan Kumar to choose from one of them. Furthermore, he insisted on Sonakshi Sinha for Kick and now he's recommending Zarine Khan to his prospective producers," a source told film expert Subhash K Jha.